2019 has been a rollercoaster year in online political advertising. Hot debates about its ethical and legal dimensions have made the headlines. Major digital advertising platforms have felt public and regulatory pressure, resulting in ambiguous responses such as Twitter’s blanket ban on paid advertising related to politics but very little mention about the harms and algorithmic biases of “organic” and “earned” media influence.

Nonetheless, political parties and organizations across Europe have spent at least €100 million to advertise on Facebook and Google for their election campaigns in 2019, based on data from the two internet giants’ own transparency reports (as of writing).

We cleaned up* and analysed the data to get a snapshot of the top spenders on each platform.

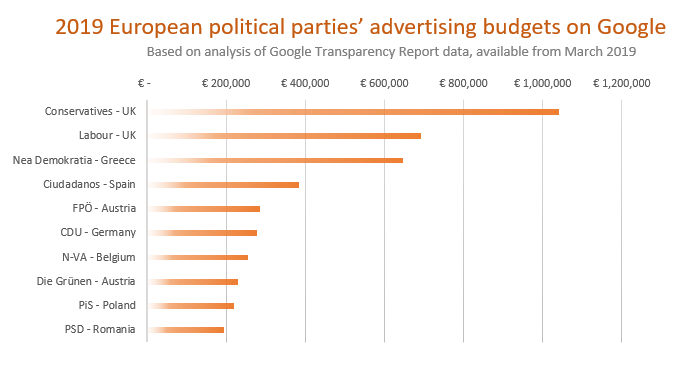

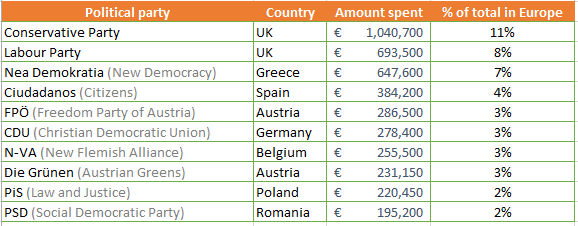

The main two British parties take the lead accounting for nearly 20% of all bills European political organizations paid directly to Google. We compared the two parties’ digital advertising performance at the UK General Election a few weeks ago following the Conservative Party’s landslide victory.

In Greece, a Google Ads bill of over €600,000 for the Nea Demokratia (New Democracy) party may have paid off at the Greek Legislative Election in July, when it won more than double its previous seats and a majority for the first time since 2007. Multiple elections took place in Spain this year, where the Ciudadanos (Citizens) party is the top spender on Google. The remaining parties among the top ten, ranging from Germany’s ruling CDU to Poland’s PiS (Law and Justice), have spent on average around €240,000.

Of course, a significant part of these budgets may have been spent also to campaign for the European Parliament elections in May.

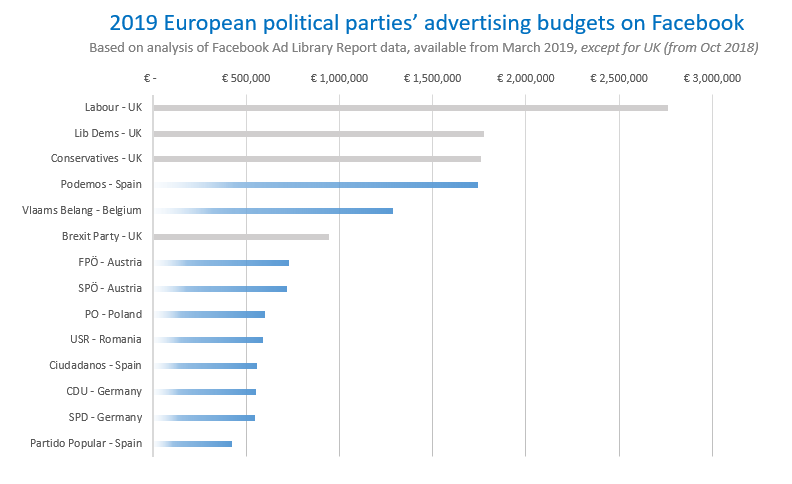

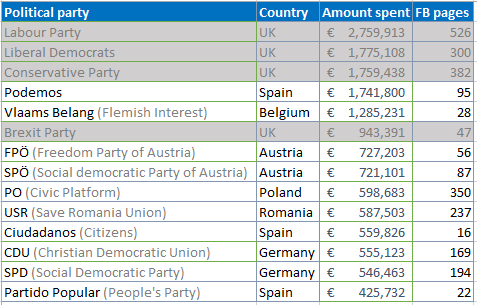

Note: because Facebook only reports a single figure for the total spend and the UK’s figures go back to October 2018, we included the top UK parties only for reference but also compare the top ten non-UK parties.

Aside from the UK parties, we see a slightly different landscape on Facebook. The top spenders after the British are the Podemos alliance in Spain and the VB / Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest) party in Belgium. The latter performed well at the 2019 Belgian federal election in May, where it saw the highest gain of new seats at the Chamber of Representatives.

Parties from Germany (where three state elections were held), Austria (which held the legislative election in September), Poland and Romania also made the list.

One of the first questions that may come to mind is how come some parties spent more on Facebook than on Google, or vice-versa.

This was an important finding in our comparison of Labour and the Conservatives at the UK General Election. Possible reasons include different preferences of the parties’ target voters, but also the different methods and levels of accuracy of targeting the electorate on the two platforms.

Also, advertising on Google is known in the industry for delivering more targeted results for less money than on Facebook.

While these statistics reveal some insights about the advertising activity of political parties, it is important to bear in mind that the available data only indicates the amount spent on paid ads – meaning direct ads for which political parties pay bills to Google and Facebook.

Our review of Google and Facebook’s political transparency reports highlighted a number of shortcomings and areas of improvement.

Another major improvement would be to include data about other types of online campaigning, e.g. making social media posts go viral. Dubious practices such as buying clicks en masse or creating tens of thousands of automated accounts (“social bots”) on Twitter that spread fake news or hyperpartisan content are thought to have contributed to the rise of populist movements like the AfD in Germany** and Vote Leave in Britain*** in recent years. Details about such practices are hardly available on company transparency reports, but have been analysed externally.

Twitter’s ban on political ads will certainly not solve the problem of political misinformation going viral through genuine-looking tweets.

Notes:

* Firstly, because Google and Facebook use different definitions for “political advertising”, it was necessary to look at each platform separately. Facebook covers all ads that mention any social or environmental issue, including corporate social responsibility messages. Secondly, platforms do not consistently add up the figures for multiple actors advertising on behalf of the same party. This requires some manual sorting and categorising, which may be imperfect. Thus, the figures for Facebook represent may be slightly under-approximated.

** The Rise of Germany’s AfD: A Social Media Analysis (Juan Carlos Medina Serrano, 2019)

*** The Brexit Botnet and User-Generated Hyperpartisan News (Bastos and Medea, 2017)

About Worldacquire

Worldacquire is a political tech firm in London providing digital strategy, advertising and analytics solutions. We managed election campaigns in Hong Kong, contributing to the 2019 landslide pro-democracy victory, and in Thailand, supporting one of the country’s first LGBTQ+ candidates, using technology to cut through electoral red tape. At the United Nations Internet Governance Forum, we called for a fair and balanced regulation of online political advertising and greater transparency of other sources of digital manipulation. We work with governments, think tanks, intergovernmental organizations and social ventures to understand and apply digital technology, A.I. and algorithms effectively and ethically.